When we first saw the old house it was easy to imagine how we might use the space, how to set out the bedrooms and bathrooms, where we would cook and where we would sleep, but the barn and stables were so full of possibilities that it seemed we would never settle on a plan for how to use them. Three years later, with the house more or less habitable, things seem a bit clearer.

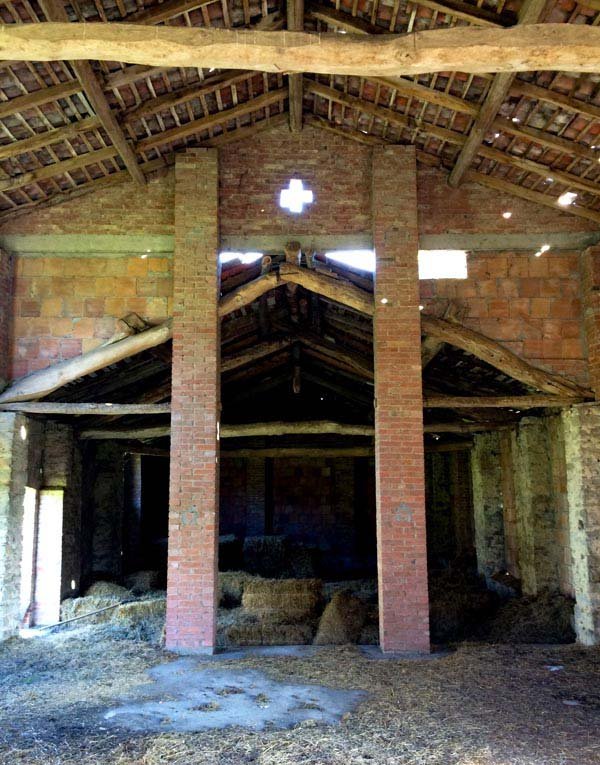

The barn would have been the centre of a small holding that supported the priests who lived in the main house. There was a porcellaio, a pig sty standing where the swimming pool now is, and a stalla for the cows, with a large hay loft above.

As soon as we saw the cow shed the individual stalls suggested themselves as a row of work stations and we began to imagine all the things you could do in a cow stall – reading, writing, painting and drawing.

The house was restored by a group of Albanian brothers, the Fratelli Albanesi, but by the time we began to turn our attention to the barns we had the great good fortune to meet a man of singular talent and purpose, Gianni Gazzotti, who we immediately recognised as a kindred spirit – the feeling was mutual.

Gianni is a very busy man, and it took a while for us to tempt him over to look at the house, but when he finally turned up he was plainly impressed. In the cellar he announced that the way the carpenters had finished the massive wooden beams on which the house rested was magnificent and showed that the work was from the 14th century. He was less pleased to see the way the modern plumbing had been installed – ‘schifo’ – crap.

Gianni invited us to his laboratory, half-an-hours drive away in Toano. Spread over the hillside below the house are hoards of ancient cotto floor tiles, chestnut and oak planks and colossal misshapen off-cuts of Carrera marble. Large workshops are stacked with pots of his own paint and the earth pigments used to colour it. There is a foundry for metalwork and hidden beneath the ground are pits of slaked lime render. We found him surrounded by schoolchildren, running a course on the art of fresco painting.

Gianni has been working on the stables for several months now and has become a firm friend, but he is still inclined to purse his lips a tut when our budget doesn’t stretch to his recommendations. He is an old-fashioned artisan whose attitudes and enthusiasms are in the tradition of Ruskin, Pugin and William Morris, but we ought perhaps to point to one of his own countrymen as an antecedent – I would suggest Cennino Cennini, a follower of Giotto in early Renaissance Florence, whose great ‘how to’ book, Il Libro dell’arte, first set down the techniques and the arduous business of making materials for the craft of painting.

We are continually reminded how fortunate we are to have found him.

Thank you for your reading. Join the conversation by posting a comment.